A small group of students and a fellow staff member have indulged me this semester by meeting up on Zoom to talk about Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia. We’ve formed something of a little community, trekking through Le Guin’s wonderful landscapes and strange worlds, recognising our own in the cracks. It has been a real joy, an oasis in my week, to think about other ways of relating to the world, to ourselves, and to others.

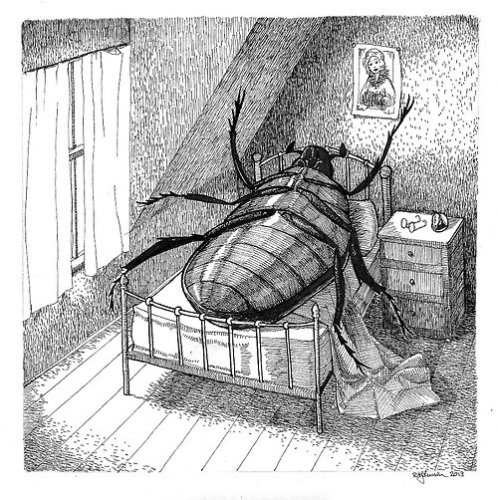

At the same time I have been working with Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis. It is a text preoccupied with the claustrophobia of isolation, of being transformed into vermin, being useless to one’s family, failing to reproduce the social order, and bearing the guilt of one’s father. Gregor Samsa wakes one morning and finds himself transformed into a big cockroach. His family can’t breathe in his presence, and only after his death are they liberated to leave the small apartment they are locked in to take in the fresh air of the outdoors. Gregor cannot even speak, his larynx doesn’t allow him, he is trapped in his own inner life.

Breathing is key to Kafka. Gregor hopes that breathing normally will restore order to things. “[W]hile he lay still, breathing lightly as if he expected total repose would restore everything to its normal and unquestionable state.” But it doesn’t work. Another figure, Odradek, who is neither person nor object, who is caught in between spaces, breathes (without lungs) but it sounds “like the rustling of leaves.” Breath is the site of Kafka’s own being ill-at-ease with himself, “I have hardly anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe.”

Coming back to me and my friends reading Le Guin, her book begins with a scene on an anarchist planet, where a physicist, Shevek, is on his way to another, capitalist planet in order to discuss physics (or so he thinks). What is apparent from the very first chapter is that walls are key to Le Guin’s description of her world. Walls that are physical, that form obstacles between worlds, but also walls that are baked into our social relations, into our language.

Shevek, in conversation with his escort to the capitalist planet, Kimoe, tries to describe how on the anarchist planet women are allowed to do all kinds of work. There are no restrictions. Kimoe is befuddled by this, protesting that surely women are not strong enough, or smart enough, to do the work. Shevek is befuddled in response, and thinks to himself,

“Kimoe’s ideas never seemed to be able to go in a straight line; they had to walk around this and that, and then they ended up smack against a wall. There were walls around all his thoughts, and he seemed utterly unaware of them even though he was perpetually hiding behind them.”

Kimoe comes up against walls in his thought that he’s unaware of, they’re unconscious. They’re baked into his language, a language people on his capitalist planet share. Shevek is encountering another world. The beauty of Le Guin’s prose, then, is bound up with her description of things, possibilities, without walls. She asks us, in a world in which there is no way of speaking as if there is a gendered division of labour, what it would mean to interact with someone whose language assumes gender is determinative of vocational possibility? It would be like interacting with someone who has unconscious walls up, they would be hiding without realising it – their whole world would be.

It’s hard to breathe, locked up at home like Gregor. The walls hem us in, the world outside is strange. Possibilities are totally circumscribed by walls surrounding my house, the imaginary wall encompassing the 5km radius around my home, and the wall that goes up after a mere 1 hour outside. The old world seems a distant memory, its possibilities totally alien. But maybe, from the distance that has opened up, we’re able to see the walls around that world. Walls that still hem us in, make us unable to think in straight lines.

I’ve not been transformed into a giant cockroach. My family have not locked me in my office just yet. I still have language. I still have others, even if mediated by Zoom. We will keep meeting, keep talking, keep imagining possibilities. We will keep letting Le Guin help us push our language to the limits, give us new ways of describing relations, because maybe we’ll catch a glimpse of the other side of the wall.

I’ll leave you with something Kafka wrote to his fiancé, Felice Bauer, about a little apartment (a bit like Gregor’s) he was hoping to get so that he might be able to write, to think, and so to catch a glimpse of paradise,

“Here, mind you, is a 2-room apartment, without kitchen, that seems in every detail to live up to even my wildest dreams. Failure to get it would be hard to bear. Though this apartment might not restore my inner peace, it would at least give me a chance to work; I dare say the gates of paradise would not promptly fly open, but in the wall I might find two slits for my eyes.”

Trinity College is a college of the University of Divinity.

University of Divinity CRICOS Code: 01037A

University of Divinity TEQSA Provider ID: PRV12135